Note: Ruza Wenclawska used different names in various aspects of her professional life, including Rose Winslow, Ruza Wenclaw, and Ruza Wenclawska. I’ll use the name, Ruza Wenclawska, for simplicity, with some notes to make clear when she used a different name.

Ruza Wenclawska was born December 15, 1889 in Suwalki, Poland. Her father, John Winslow was Lithuanian, and her mother Blanche was Polish. One of eleven children, her family immigrated to the United States when she was eight months old. The family name was most likely originally Wenclaw, but they Americanized it to Winslow sometime after their arrival in the United States. Wenclawska used the name Rose Winslow in her early life and during her time as a labor activist and suffragist.

Her family first lived in Pittsburgh, then in Shenandoah, Pennsylvania where her father worked in the mines. They moved to Philadelphia about 1895, where Wenclawska began working in a hosiery factory at age 11. She worked in the factory until about age 18, when she was diagnosed with tuberculosis and was admitted to a sanitarium. Several other members of her family also had tuberculosis, including her mother, and an older brother and sister, who both died in tuberculosis hospitals. Sometime after her release from the sanitarium she made an emotional appeal in a speech at a fundraiser for tuberculosis relief in Philadelphia, bringing her to the attention of the Philadelphia Consumer League, which hired her as a factory inspector.

By 1910 she was in New York City, where she worked as a labor activist and became a member of the Womens’ Trade Union League in 1913. She is mentioned by the New York Tribune as one of the labor activists organizing a garment workers strike in January 1913, in charge of the Union Hall at 177 East Broadway, giving out sandwiches provided by a local women’s suffrage organization.

She became a popular and fiery speaker on labor rights and suffrage, known for her down to earth speaking style. Her fame as an orator grew throughout 1913; she spoke at New York’s Cooper Union in April, addressed the National American Woman Suffrage Association in November, and spoke at hearings in both the Pennsylvania General Assembly and the United States House of Representatives.

Her speech on suffrage and working women to NAWSA brought her to the attention of the Congressional Union for Woman Suffrage, which hired her as an organizer. In March 1914 she was part of a delegation of working women who marched to the White House to meet with Woodrow Wilson, and was one of the four women chosen to speak to the President. In September 1914 she and Lucy Burns traveled to California to set up a Congressional Union headquarters in San Francisco. She spoke in cities throughout California on suffrage and working women, encouraging women to join the Congressional Union.

In 1915 she was one of the speakers on the suffrage Justice Bell tour of Pennsylvania. In 1916 she was one of the speakers sent by the National Woman’s Party to support Inez Milholland’s tour of the western states. Winslow spoke throughout Arizona, taking over Inez Milholland’s stop in Phoenix after she collapsed in Los Angeles. Winslow also became ill on the tour and canceled two appearances. Despite being told by a doctor to rest more and limit herself to speaking once a day, she sometimes spoke for two to three hours at a time.

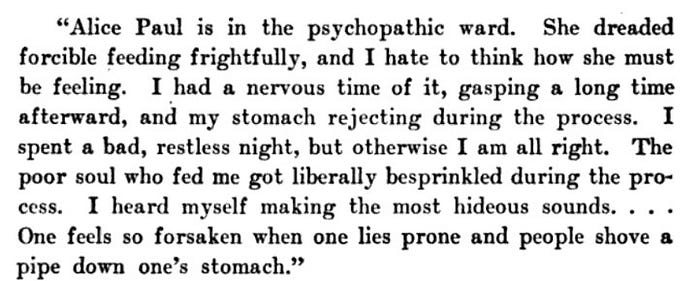

In 1917 she was one of the suffragists arrested for picketing the White House and sentenced to 7 months in jail. With Alice Paul, she led a hunger strike and was forcibly fed. Her letters describing her treatment in jail were smuggled to her husband and are reprinted in Doris Stevens’ “Jailed for Freedom.”

Wenclawska married Phillip “Phil” Lyons, sometime before 1910. According to newspaper accounts, they met when he stopped to listen to one of her street corner speeches in New York and was enlisted to carry the soap box she stood on. Lyons, raised in Philadelphia, was also from an immigrant family. He was one of the officers of a New York company that sold loose-leaf binders, though he is remembered in the memoir of artist Guy Pène du Bois as an “amateur painter and dandy.” Wenclawska and her husband lived at several addresses in Greenwich Village, including 37 Bank Street, where they were part of the Village’s radical bohemian community.

Around 1917 Wenclawska started to publish poetry and work as an actor in New York. She used the name Ruza Wenclaw as an actress and poet. She published at least seven poems in 1916 and 1917. Her most reprinted poem The New Freedom for Women, was originally published in The Suffragist but most of her published poetry appeared in The Masses, the radical magazine published in Greenwich Village by Max Eastman.

While living in the Village, Wenclawska began a career as an actress. She appeared primarily in productions by the Provincetown Players, the Greenwich Village theater company that launched the careers of Susan Glaspell and Eugene O’Neill. Her husband Phil Lyons also occasionally played small parts. She appeared in 5050 in January 1918 and The Rescue in December 1918 with the Provincetown Players. She appeared on Broadway at the Plymouth Theater in Redemption, starring John Barrymore, in October 1918.

In 1921 she went to Europe to join her husband, who had gone to England, France, and Italy, ostensibly as a sales trip for his company. According to her passport application she planned to visit Britain, France, Italy, Switzerland and Gibraltar to work and study.

In 1924 she began using her full name, Ruza Wenclawska, professionally and that is how she is billed for the rest of her career. In that year she appeared with the Provincetown Players in The Spook Sonata in January 1924 and Fashion in February 1924.

Her final role was a small part in the premier of Eugene O’Neill’s Desire Under the Elms. The Provincetown Players production opened November 11, 1924, when it transferred to Broadway in 1925 Wenclawska remained with the show.

Sometime in 1925 she made another trip to Europe, returning in December 1925 with her husband, but their marriage was soon to end in divorce. By September 1926 Phil Lyons was back in Paris and engaged to a publisher’s daughter from Chicago he met while studying art.

In the 1930 census Ruza Wenclawska is listed as a patient at the Central Islip State Hospital. Records of New York state hospitals are not publicly available, but probably the illness which had forced her to quit factory work as a teenager finally caught up with her and she was in the hospital’s tuberculosis ward. She died on April 16, 1934 in Islip, New York.

Notes: I started researching Ruza Wenclawska after I saw the musical Suffs in New York. I googled all the suffragists I hadn’t heard of before, and was very disappointed with the limited information on Wenclawska, especially the fact that no one seemed to be sure when she died. This short bio is the result of my research so far.

Wenclawska discusses her early life in a speech reported in: Stirring Scenes as New Liberty Bell Tours the Valley, The Pittston Gazette, Sept. 11, 1915, p. 6. Also: Miss Winslow on the Issue of Suffrage, The New Castle Herald, Aug. 17, 1915, p.10.

Census records:

1900 US Federal Census, Philadelphia Ward 32, as Rosa Vamslow

1910 US Federal Census, Manhattan Ward 22, New York as Rose W. Lyons

1920 US Federal Census, Manhattan Assembly District 10, New York as Rose Lyons

1925 New York State Census, New York as Ruza Wenclawska

1930 US Federal Census, Islip, New York as Ruza Wenclawska

Directories: 1917 New York City directory available on ancestry.com as Rose Winslow

Passport application: 1921, available on ancestry.com an familysearch.org as Ruza Lyons

Proud Girl Strikers Reject Philanthropy, The New York Tribune, Jan. 18, 1913, p. 6.

Cupid of the Cause Lurks in Soapbox, The New York Tribune (October 1, 1913) p. 10

Annual report of the Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art, June 1914, p. 105

Information on Provincetown Players including cast lists for productions: Helen Deutsch & Stella Hanau. The Provincetown: A Story of the Theatre, Farrar and Rinehart, 1931.

Cast list for Desire Under the Elms from The Billboard, Aug. 14 1926, p. 61 https://hdl.handle.net/2027/iau.31858030435931

Phil Lyons’ engagement is in The Chicago Tribune, Sept. 19, 1926, pt. 2, p. 4.

Death: New York Death Index 1934 https://archive.org/details/New_York_State_Death_Index_1934/page/n1246/mode/1up

Poetry:

The New Freedom for Women, The Suffragist (September 30, 1916), p. 4

Fire-Bird, The Masses (October 1916), p. 9

The Orator, The Masses (April 1917), p. 41

Children Playing, The Masses (April 1917), p. 42

Regret, The Masses (June 1917), p. 50

Hills, The Masses (July 1917), p. 3

The Mountains, The Masses (April 1917), p. 25

This article was originally published on Medium.com